© 2025 Roz UpdatesbyTETRA SEVEN

* All product/brand names, logos, and trademarks are property of their respective owners.

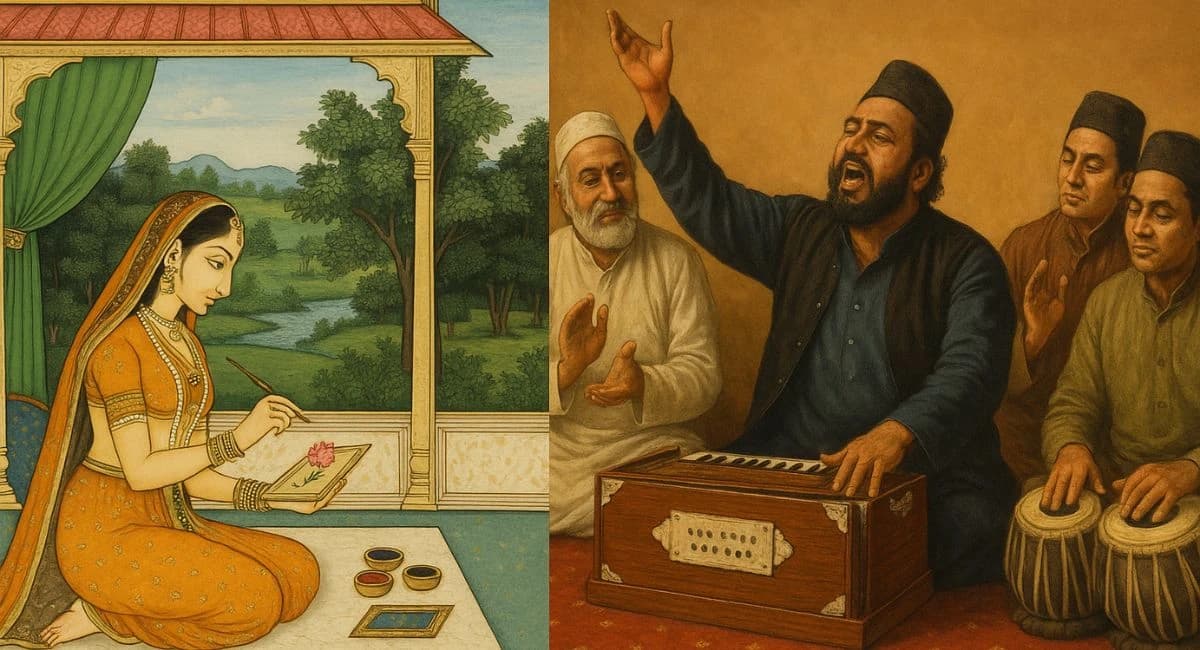

In the bustling lanes of Lahore, under the shadow of Mughal domes and the scent of fresh paint and old books, a quiet revolution is unfolding. From intricately detailed miniature paintings exhibited in modern galleries to the soulful strains of Qawwali echoing through restored havelis, Pakistan is witnessing a powerful comeback of its classical art forms. This revival isn’t just nostalgic; it’s a dynamic cultural movement reclaiming heritage, identity, and expression in the face of modernity’s relentless march.

Once preserved only in textbooks or whispered through family traditions, classical art in Pakistan is re-emerging with fresh vitality. Miniature painting—once the chosen medium of Mughal emperors—is no longer confined to dusty archives. Thanks to the vision of institutions like the National College of Arts (NCA) and bold reinterpretations by contemporary artists, this meticulous craft is reaching new audiences, blending ancient techniques with modern themes and aesthetics.

Meanwhile, Qawwali, the Sufi devotional music that once defined spiritual life in the subcontinent, is experiencing its own renaissance. From Sufi shrines to urban concert halls, the rhythmic clapping, hypnotic melodies, and poetic lyricism of Qawwali are captivating both old followers and curious newcomers. It’s not merely a genre of music—it’s a portal into centuries of mysticism, love, and divine connection.

This blog explores the vibrant intersection of these two enduring art forms: the visual poetry of miniature paintings and the auditory ecstasy of Qawwali. What ties them together isn’t just history, but a shared spirit of storytelling, devotion, and resistance. Together, they represent more than a cultural comeback—they signal a return to roots, a rediscovery of soul, and a reawakening of Pakistan’s rich artistic legacy.

Miniature painting in South Asia is one of the most refined visual traditions, rooted in the opulent courts of the Mughals. These tiny masterpieces weren’t just decorative—they were visual manuscripts, spiritual epics, and political commentaries all at once. Characterized by their intricate detail, vivid colors, and narrative power, these works portrayed royal life, folklore, nature, and mysticism with unmatched precision.

During the Mughal era, emperors like Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan patronized vast ateliers of painters, blending Persian, Indian, and Islamic artistic influences. Each brushstroke was painstakingly planned, with natural pigments ground from minerals, plants, and gold leaf. But after the decline of the Mughal empire and the advent of British colonial rule, the patronage system collapsed, and miniature painting, like many indigenous crafts, was marginalized.

In the late 20th century, Pakistan saw the unexpected reawakening of this ancient form—thanks largely to the National College of Arts (NCA) in Lahore. Under the guidance of professors like Zahoor ul Akhlaq and Salima Hashmi, a new generation of artists began reinterpreting traditional miniature techniques through contemporary lenses.

This “neo-miniature” movement gave rise to globally recognized artists like Shahzia Sikander, Imran Qureshi, Aisha Khalid, and Saira Wasim. Their work challenges political narratives, identity, gender roles, and post-colonial realities—while staying true to the discipline of the miniature format. Suddenly, what was once perceived as a relic of the past became a tool for sharp, modern storytelling.

The revival is not limited to elite galleries or academia. Today, exhibitions of miniature art are held in Lahore’s Alhamra Arts Council, Karachi’s VM Art Gallery, and Islamabad’s PNCA, drawing crowds of all ages. Internationally, these artists exhibit in New York, London, and Dubai—proving that miniature painting has not only survived but evolved as a globally relevant art form.

This reimagined legacy honors tradition while daring to challenge it. In the careful stroke of a squirrel-hair brush, one can witness a dialogue between eras—a fusion of past and present, heritage and innovation.

Qawwali, the devotional music of the Sufis, has long been a spiritual heartbeat of the subcontinent. Born in the 13th century in the shrines of Chishti Sufis, it was envisioned not as entertainment, but as a powerful vehicle for divine union. Rooted in Persian, Arabic, Hindi, and Punjabi poetic traditions, Qawwali blends lyrical devotion with rhythmic intensity, creating a musical experience that transcends the physical world.

Structured with a slow, deliberate build-up—starting with a hamd (praise of God), followed by naat (praise of the Prophet), and culminating in emotionally charged love poems (ghazals) or Sufi kalams—Qawwali is immersive by design. The harmonium, tabla, dholak, clapping, and the compelling vocals of a lead singer (often backed by a chorus) weave together a hypnotic soundscape. It’s not uncommon for listeners to enter trance-like states, overcome by the spiritual charge of the performance.

Historically, names like Amir Khusro, regarded as the pioneer of Qawwali, and later, the Sabri Brothers and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, turned this genre into an international phenomenon. Nusrat, in particular, revolutionized Qawwali by bringing it to global platforms—collaborating with Western artists, composing for films, and expanding its reach without compromising its sacred roots.

Today, young Qawwals like Fareed Ayaz, Abu Muhammad, and Rahat Fateh Ali Khan carry this legacy forward. They perform not only in traditional Sufi shrines like Data Darbar and Sehwan Sharif but also in curated festivals, global concert halls, and digital platforms. Their music continues to be a call for unity, love, and spiritual awakening in an often fragmented world.

What’s striking today is the resurgence of Qawwali as a lifestyle movement. Cities like Lahore and Karachi host regular Qawwali nights in cafes, cultural centers, and restored havelis. Organizations like PNCA and Lok Virsa are spearheading heritage festivals featuring classical performances. Sufi shrines, once neglected, are reclaiming their cultural significance as pilgrimage and performance spaces.

Moreover, fusion initiatives—where Qawwali blends with jazz, electronic, or orchestral music—are introducing it to younger, global audiences without losing its soul. This return isn’t a trend—it’s a reclamation of identity, where art meets devotion, and performance becomes prayer.

In an age dominated by fleeting trends and digital noise, the resurgence of classical art forms like miniature painting and Qawwali offers a grounding force—a reminder of where we come from, who we are, and the stories that shape our soul. These aren’t just traditions preserved in glass cases or confined to historic monuments—they are living, evolving expressions of identity, spirit, and cultural resilience.

Miniature painting, once a regal past-time confined to royal ateliers, now lives on through contemporary brushstrokes that challenge norms and ignite dialogue. Each tiny detail is a testament to an artistic discipline that refuses to be forgotten. At the same time, Qawwali, with its pulsating rhythms and transcendent lyrics, continues to stir hearts in shrines and urban cafes alike, creating shared spaces of emotional release and divine connection.

Together, these art forms are more than a revival—they are a cultural reawakening. They remind us that heritage isn't static; it's a dialogue between generations. It is in our hands to nurture it, reinterpret it, and most importantly, participate in it.

So attend that Qawwali night. Visit that miniature painting exhibition. Share that local artist’s work. Because when you engage with classical art, you don’t just witness history—you help write its next chapter.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!